Every year for Christmas, my dad gave my brother Tony and me a brand new football. We would throw and catch that ball 1,000 times every day for the entire year. Dad had one rule:

“Don’t let the ball touch the ground.”

It wasn’t a threat, it was a life lesson.

That’s because Dad was not going to buy another football until the next Christmas. No matter what happened. We couldn’t afford it. At a young age, Tony and I both knew what was at stake.

As a result, we learned to treat the ball and the game with respect. The rule taught us that actions have consequences and that things wouldn’t always go our way. We might drop the ball, but we could pick it up and start our game again.

I still have this rule with my own son and daughters.

But when I talk about it with other parents, their reaction reveals why so many young people are struggling with small and larger challenges.

Dealing with failure is a life skill, but the relentless pressure on kids to succeed makes them fearful of failure, and unable to recover from adversity. The widely reported epidemic of depression, mental illness, and suicide attempts by college students is rooted in that fear.

Several years ago, I was at a kids’ birthday party in a swanky LA neighborhood playing catch with my son, Axel. Axel was about 3 at the time, and we were tossing this little plastic football back and forth and Axel dropped it.

So I told him, “Axel, don’t let the ball touch the ground.”

Axel just nodded his head, picked up the ball, and kept on passing it back to me.

One of the dads at the party came over and challenged me: “Why would you say that to that boy?”

I said, “That boy is my son, and I say it because that’s a rule in our house. We don’t let the ball the touch the ground.” This dad grew more upset and said, “Why would that be a rule in your house?”

“Because we dedicate our lives to it,” I told him, and explained my dad’s thinking on the subject.

This dad mockingly asked, “So how did that work out for you?”

“Well, it worked out pretty good. My brother and I both played in the NFL.”

Right after that I told my wife, Dawn, that we were moving out of the neighborhood.

Why do we settle for mediocrity when it comes to our lives and our kids’ lives?

Why do we, as parents, do everything we can to make sure our kids don’t feel the pain of rejection and struggle?

If we want our kids to succeed, we have to let them struggle. That means the ball will hit the ground. When it does, we can help them by setting a new goal, not by punishing them for failing to achieve it, nor by neglecting to set any goal at all, for fear of hurting their feelings.

In Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise, Anders Ericsson talks about the need for “purposeful practice” and “well-defined, specific goals” in order to be the best. And a crucial part of purposeful practice is getting our kids out of their comfort zones. Ericsson cites a study with physicians 20-30 years out of school who perform worse on certain objective measures of performance v. those 2-3 years out of medical school.

Why? As Ericsson notes: “It turns out that most of what doctors do in their day-to-day practice does nothing to improve or even maintain their abilities; little of it challenges them or pushes them out of their comfort zones.”

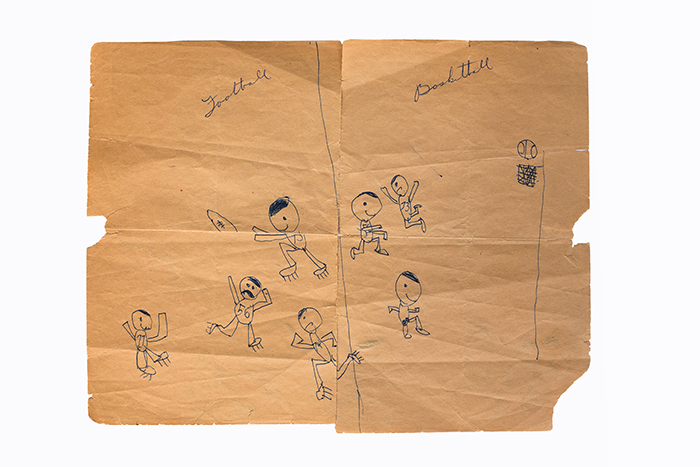

As a kid, I set myself a big goal that definitely pushed me outside my comfort zone: to be the best free safety in the National Football League. I wrote down that goal in a notebook that I still have today. Twenty years later, I made All-Pro at that position.

And yes, the ball touched the ground plenty of times along the way.

What is your child’s dream?

Is it singing, is it guitar, is it ballet or tennis? Is it mathematics or creative writing? Is it astronomy?

Have your child write it down, and draw a picture of themselves doing what they dream. Doing so will make the goal more real.

Once your child declares his or her dream, your job is to help them achieve it.

Ask your son or daughter:

- “Did you catch your thousand balls today?”

- “Did you rehearse today?”

- “Did you do your 200 math exercises?”

- “Did you go to the library and check out that book about space?”

You are not being a “pushy parent.” You're setting the bar. You’re helping your child reach the goal he or she has written down. But it won’t happen quickly, and it won’t happen at all without doing the work of preparing, of succeeding and failing and trying again.

Playing in the NFL meant practicing for thousands of hours to play one hour on Sunday. After I retired, I became an actor: Same deal. I put in thousands of hours to perform for an hour or two on stage.

According to Ericsson, what separates the best from the “better,” is the hours of practice that the students put in. For example, in one study from Peak, better violin students on average put in 5,301 hours of practice before they entered a music academy. The best had practiced for 7,410 hours. And to take it a step further: those students who stuck with their practice schedule during their preteen and teen years were more likely to be in that best group.

Say your kid wants to be the best trumpet player in the world. That’s hard. But if you focus on the practice instead of the performance, eventually they will fall in love with their own improvement. If they say “I suck,” your answer is: No, you don't suck, you just haven't played enough, you haven't practiced enough. The process is as important as the result. Failure is part of that process, not an end point, but a step along the way.

By the way—even if your child doesn’t become the best trumpet player in the world, teaching them to stay focused on their goals benefits them in so many other ways in life, including how to show up for work, marriage, their own kids.

The great dance teacher Martha Graham once said:

“No artist is pleased. [There is] no satisfaction whatever at any time. There is only a queer divine dissatisfaction, a blessed unrest that keeps us marching and makes us more alive than the others.”

The same holds true in every other field: Sports or science, music or marketing, business or brain surgery. The best keep making incremental improvements, always risking failure, always moving toward a higher goal.

And when the ball hits the ground, they don’t stop playing. They pick it up and throw it again.

Take Action:

Whether you're a parent or a Player who's working on becoming the Best, I want to hear what you think. Do you agree with the thoughts I shared? Where in your life do you need to pick up the ball and throw it again?

Leave me a note in the comments below!

|